The moon has never been more crowded—at least, not in terms of who wants to get there. More than five decades after Neil Armstrong’s iconic first steps, humanity is witnessing an unprecedented surge of lunar ambition. But this time, the players have changed. The new race to the moon isn’t just about flags and footprints. It’s about billion-dollar corporations, emerging space powers, and a fundamental reimagining of who gets to explore the cosmos and why.

Where the Apollo era was defined by Cold War rivalry between two superpowers, today’s lunar landscape is a complex web of private companies with rockets to sell, nations seeking technological prestige, and an underlying question that grows more urgent with each passing launch: Who owns the future of space exploration?

The Shifting Paradigm: From Governments to Billionaires

For most of human history, space exploration was the exclusive domain of nation-states. The resources required, the technological expertise needed, and the sheer audacity of the endeavor meant that only governments—with their massive budgets and national imperatives—could seriously contemplate leaving Earth’s atmosphere. The Space Race of the 1960s epitomized this era: NASA and the Soviet space program locked in a prestigious competition that was as much about demonstrating ideological superiority as it was about scientific discovery.

That paradigm has shattered.

Today, private corporations are not merely supporting government space programs—they’re competing with them, often surpassing them in innovation, efficiency, and ambition. This transition didn’t happen overnight. It emerged from decades of gradual policy shifts, technological maturation, and the vision of entrepreneurs who saw space not as a frontier for national pride alone, but as the next great market opportunity.

“The question is no longer whether private companies can reach the moon, but whether governments can keep up with them.”

The catalyst for this transformation can be traced to several key developments. NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, initiated in the 2010s, marked a philosophical shift in how the world’s premier space agency approached spaceflight. Rather than building and operating every component of its missions, NASA began contracting with private companies to develop spacecraft and launch services. This opened the floodgates for commercial space ventures, providing both funding and legitimacy to companies that had previously existed on the fringes of the aerospace industry.

The Private Titans: SpaceX, Blue Origin, and the New Space Economy

SpaceX: The Disruptor-in-Chief

No company embodies the private space revolution more than SpaceX. Founded by Elon Musk in 2002 with the explicit goal of making humanity a multi-planetary species, SpaceX has methodically dismantled assumptions about what private companies could achieve in space. The company’s Falcon 9 rocket, with its revolutionary reusable first stage, has become the workhorse of the commercial space industry. Its Falcon Heavy has launched payloads that once required government-built rockets. And its Dragon spacecraft has ferried NASA astronauts to the International Space Station, ending America’s decade-long dependence on Russian Soyuz vehicles.

But SpaceX’s lunar ambitions extend far beyond Earth orbit contracts. The company’s Starship vehicle—a fully reusable super-heavy-lift launch system—is being designed with lunar missions at the forefront. NASA has selected a modified version of Starship as the Human Landing System for its Artemis program, which aims to return astronauts to the lunar surface. The irony is palpable: America’s government space agency will rely on a private company’s spacecraft to achieve its flagship exploration goal.

SpaceX’s approach represents a fundamental departure from traditional aerospace. Where legacy contractors built exactly what NASA specified, often at cost-plus arrangements that incentivized expense over efficiency, SpaceX develops its hardware independently, maintains ownership of its technology, and sells services rather than products. This model has allowed the company to iterate rapidly, fail publicly (its Starship test campaign has featured several spectacular explosions), and ultimately advance at a pace government programs struggle to match.

Blue Origin: The Patient Competitor

If SpaceX is the aggressive disruptor, Blue Origin represents the methodical long game. Founded by Jeff Bezos in 2000—two years before SpaceX—Blue Origin has pursued space access with a philosophy summed up in its Latin motto: “Gradatim Ferociter,” or “Step by Step, Ferociously.” While it hasn’t matched SpaceX’s launch cadence or public visibility, Blue Origin has made steady progress toward its own lunar ambitions.

The company’s Blue Moon lunar lander concept showcases a different approach to reaching the moon’s surface. Designed to deliver large payloads to precise locations, Blue Moon emphasizes reliability and payload capacity over dramatic innovation. Blue Origin has also developed the New Glenn rocket, a partially reusable heavy-lift launch vehicle designed to compete with SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and eventually support lunar missions.

What makes Blue Origin particularly interesting in the new space race is its emphasis on lunar infrastructure. Bezos has been vocal about his vision of moving heavy industry off Earth and into space, with the moon serving as a crucial waystation and resource depot. The company’s proposed “Blue Alchemist” project aims to use lunar regolith to produce solar cells and extract oxygen—potentially game-changing capabilities for establishing a sustained lunar presence.

Unlike SpaceX’s single-founder driver approach, Blue Origin has faced criticism for a more deliberate development timeline. Yet this patience may prove strategic. As SpaceX focuses on Mars and rapid iteration, Blue Origin is positioning itself as the reliable partner for sustained lunar operations—potentially carving out a distinct niche in the cislunar economy.

“We will have to leave this planet, and we’re going to leave it, and it’s going to make this planet better.” – Jeff Bezos on the rationale for Blue Origin

The Supporting Cast: A Constellation of Competitors

Beyond the two most prominent players, a constellation of companies is emerging to fill various niches in the lunar economy. Rocket Lab, with its Electron small satellite launcher and developing Neutron medium-lift vehicle, aims to provide affordable access to cislunar space. Firefly Aerospace has won NASA contracts to deliver payloads to the lunar surface. Intuitive Machines made history in 2024 by executing the first commercial lunar landing, demonstrating that the technical barriers to reaching the moon have fallen dramatically.

These companies represent more than just redundancy—they signal the maturation of space access as a genuine industry. Where Apollo required the mobilization of an entire nation’s resources, today’s lunar missions can be executed by companies with a few hundred employees and capital raised from private investors. This democratization of space access is perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of the new space age.

The National Players: Pride, Prestige, and Strategic Positioning

While private companies dominate headlines, national space programs remain formidable players with distinct advantages and motivations. The current lunar race is perhaps best understood not as private versus public, but as a complex interplay between commercial ambition and national interest.

NASA’s Artemis: Government Ambition in a Commercial Age

NASA’s Artemis program represents America’s official return to the moon. Named after Apollo’s twin sister in Greek mythology, Artemis aims to land the first woman and first person of color on the lunar surface, establish a sustainable presence, and use the moon as a proving ground for eventual Mars missions. The program’s architecture reveals how thoroughly the commercial space paradigm has penetrated even government flagship missions.

The Space Launch System (SLS)—NASA’s own super-heavy-lift rocket—represents old-space thinking: a government-designed vehicle built by traditional contractors using cost-plus contracts. It’s powerful, reliable, and eye-wateringly expensive, with per-launch costs estimated to exceed $4 billion. By contrast, Artemis will rely on commercial providers for crew and cargo delivery, lunar landers, and potentially even alternative launch vehicles as the program matures.

This hybrid approach reflects NASA’s evolution from space agency to space orchestrator. The agency’s role increasingly involves setting exploration goals, providing funding, and coordinating between various commercial and international partners rather than building and operating every system itself. Whether this model proves more effective than Apollo’s centralized approach remains one of the great experiments of modern space policy.

China’s Lunar Ambitions: The Silent Competitor

While Western attention focuses on the SpaceX-Blue Origin rivalry, the most significant national competitor in the new space race is China. The China National Space Administration (CNSA) has methodically pursued lunar exploration through its Chang’e program, named after the Chinese moon goddess. Unlike the American approach of commercial partnerships, China’s program represents pure state-directed ambition—and it’s been remarkably successful.

The Chang’e missions have progressively demonstrated increasingly sophisticated capabilities. Chang’e 4 achieved the first landing on the moon’s far side in 2019. Chang’e 5 successfully returned lunar samples in 2020—China’s first sample return from beyond Earth orbit. Chang’e 6 repeated this feat from the far side in 2024, showcasing technical prowess that few nations can match. China has announced plans for crewed lunar missions in the 2030s and speaks openly about establishing a permanent International Lunar Research Station.

What makes China’s lunar program particularly significant is its integration with broader strategic objectives. Unlike the Cold War space race, which was primarily about prestige and demonstrating technological superiority, China’s space ambitions are tied to long-term economic and geopolitical goals. The country views space capabilities as essential to its aspiration for technological leadership, and lunar resources—particularly helium-3, which could theoretically fuel future fusion reactors—figure prominently in Chinese strategic thinking.

China’s approach also highlights a fundamental difference from the commercial space model. Where private companies must eventually generate returns for investors, state-directed programs can pursue longer-term objectives independent of quarterly profit expectations. This patient capital approach allows for sustained investment in technologies and capabilities that may take decades to pay off—a potential advantage in the marathon of space development.

India’s Chandrayaan: Efficiency and Emergence

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has emerged as an unexpected but impressive player in lunar exploration. India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission successfully landed on the moon’s south polar region in 2023, making India the fourth country to soft-land on the lunar surface and the first to do so near the south pole—a region of intense interest due to potential water ice deposits.

What sets ISRO apart is its remarkable cost-efficiency. Chandrayaan-3 was developed and launched for approximately $75 million—less than the budget of many Hollywood films and a fraction of what comparable Western missions cost. This efficiency stems from India’s lower labor costs, streamlined bureaucracy, and engineering culture that emphasizes practical solutions over gold-plating every component.

India’s lunar program serves multiple national objectives. It demonstrates technological capability, enhances national prestige, inspires a new generation of engineers and scientists, and positions India as a potential low-cost launch and mission provider in the emerging space economy. ISRO has explicitly pursued commercial partnerships, offering launch services and potentially positioning itself as the “budget option” for nations and companies seeking lunar access without Western or Chinese dependence.

“India’s moon landing isn’t just a national achievement; it’s a demonstration that space exploration is no longer limited to the wealthiest nations.”

Japan, Russia, and the Second Tier

Other national programs add complexity to the lunar landscape. Japan’s JAXA has partnered with ISRO on lunar missions and is developing its own exploration capabilities, positioning itself as a key partner in both American and international lunar initiatives. The United Arab Emirates, despite being a small nation, has invested heavily in space capabilities and established partnerships with both American commercial providers and various national space agencies.

Russia, once the Soviet Union’s space superpower, has seen its lunar ambitions stumble. The Luna-25 mission—Russia’s first lunar landing attempt in nearly five decades—crashed into the moon’s surface in 2023, highlighting the atrophy of capabilities during the post-Soviet era. While Russia announced plans for future missions and a potential lunar base collaboration with China, its space program faces economic constraints and technological challenges that have diminished its once-dominant position.

The Prize: Why the Moon Matters Now

Understanding the new race to the moon requires grasping why the lunar surface has suddenly become valuable after decades of relative neglect following Apollo. The answer lies in a convergence of technological capability, resource scarcity, and strategic thinking about humanity’s long-term future.

Water: The Unexpected Game-Changer

The most significant lunar discovery of recent decades came not from Apollo astronauts but from orbital spacecraft: water ice in permanently shadowed craters near the lunar poles. This discovery transformed the moon from a barren rock into a potential resource depot. Water isn’t just essential for sustaining human life—it can be split into hydrogen and oxygen, creating rocket propellant. A lunar propellant production facility could dramatically reduce the cost of deep space missions by eliminating the need to haul all fuel from Earth’s deep gravity well.

This is why multiple missions, both governmental and commercial, are targeting the lunar south pole. The potential to extract and process lunar water represents the difference between the moon as a destination and the moon as a gateway. It’s the key to making lunar bases economically sustainable and to enabling the broader solar system exploration that both national space agencies and commercial visionaries pursue.

Strategic High Ground

The moon also represents strategic positioning in an increasingly contested space domain. As satellites become essential to military operations, communications, and economic activity, the ability to operate in cislunar space—the region between Earth and the moon—gains strategic importance. The moon offers potential locations for observation, communications infrastructure, and potentially even space-based resources that could be denied to competitors.

This strategic dimension explains why nations like China view lunar capabilities not merely as scientific achievements but as essential components of comprehensive space power. It also explains why the Artemis Accords—NASA’s framework for international cooperation in lunar exploration—have taken on geopolitical significance, with nations effectively choosing between American-led and Chinese-led frameworks for space governance.

The Long Game: Mining, Manufacturing, and Mars

The most ambitious visions for lunar development extend beyond water extraction to full-scale resource utilization. Lunar regolith contains metals, silicon, and rare earth elements. While transporting these materials to Earth may never be economically viable against terrestrial mining, using them for in-space manufacturing could prove revolutionary. Building spacecraft, habitats, and infrastructure from lunar materials rather than launching everything from Earth could reduce costs by orders of magnitude.

The moon also serves as a testing ground and waystation for Mars missions—SpaceX’s ultimate objective and an increasingly common theme in space policy discussions. Establishing reliable life support systems, resource extraction technologies, and long-duration habitation on the moon provides essential experience for the far more challenging journey to Mars. The moon is three days away; Mars is six months. Failures on the moon mean a difficult but possible rescue; failures on Mars likely mean death.

This progression—Earth orbit to lunar orbit to lunar surface to Mars—represents the roadmap that both commercial and governmental space programs increasingly follow. The moon isn’t the final destination; it’s the training facility and supply depot for humanity’s expansion into the solar system.

The Collision Point: Cooperation, Competition, and Conflict

As lunar traffic increases, the frameworks governing space activity face unprecedented stress. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the primary international agreement on space law, was drafted when only two nations could reach orbit. Its provisions—no national appropriation of celestial bodies, space for peaceful purposes, liability for damage—were adequate for an era of limited space activity by nation-states. They may prove inadequate for an era of commercial exploitation and proliferating space powers.

Property Rights in a Legal Vacuum

Who owns lunar resources? The Outer Space Treaty prohibits nations from claiming territory, but it doesn’t explicitly address private property rights or resource extraction. The United States has passed legislation allowing American companies to keep resources extracted from celestial bodies, while international consensus on this interpretation remains elusive. China and Russia have not signed the Artemis Accords, which include provisions on resource utilization and safety zones, instead pursuing their own framework through the proposed International Lunar Research Station.

This legal ambiguity creates practical problems. If SpaceX establishes a propellant production facility in a lunar crater containing water ice, can a Chinese mission set up operations 500 meters away? What constitutes interference with another party’s operations? Without clear frameworks, lunar “land rushes” could create dangerous situations where misunderstandings escalate due to the high stakes and limited communication.

The Dual-Use Dilemma

Space technology is inherently dual-use—the same capabilities that enable exploration can support military objectives. Launch vehicles are fundamentally similar to intercontinental ballistic missiles. Satellites that map lunar resources could redirect to spy on terrestrial facilities. Lunar bases could theoretically host sensors or even weapons, though current international law prohibits nuclear weapons in space.

This dual-use nature means that even purely commercial or scientific lunar activities carry strategic implications. China’s lunar program, while officially civilian, benefits China’s overall space capabilities, including those with military applications. American concerns about Chinese space capabilities influence NASA’s partnerships and technology sharing policies. The result is a lunar environment where cooperation exists alongside underlying strategic competition.

“The Outer Space Treaty was written for a world of two spacefaring nations. It’s being tested by a world of dozens.”

Debris, Interference, and the Tragedy of the Commons

Even without intentional conflict, increased lunar activity raises practical concerns. Each landing mission kicks up dust that could contaminate nearby equipment or experiments. Radio transmissions could interfere with sensitive astronomical observations that the moon’s far side makes uniquely possible. Historical landing sites from Apollo and Soviet missions hold cultural and historical value—should they be protected, and if so, by whom?

These questions mirror terrestrial environmental and heritage debates, but with the added complexity of operating in a legal framework never designed to address them. As lunar traffic increases—some projections suggest dozens of missions annually within a decade—the need for updated governance frameworks becomes urgent. Whether such frameworks emerge through existing international bodies, new treaties, or simply customary practice among spacefaring entities remains uncertain.

What This Means for Humanity’s Next Chapter

The implications of the new space race extend far beyond which flag gets planted or which company’s logo adorns the first lunar propellant depot. The transition from government-dominated to commercially-driven space exploration represents a fundamental shift in how humanity expands beyond Earth.

Democratization or Oligarchy?

Enthusiasts point to the democratizing effect of commercial space. Launch costs have plummeted, enabling smaller nations, universities, and even private citizens to access space. Satellite constellations provide global internet access, potentially connecting billions to the digital economy. The skills and technologies developed for space applications spin off into terrestrial benefits, from materials science to life support systems relevant for Earth’s environmental challenges.

Critics counter that the new space age concentrates power in the hands of billionaire entrepreneurs whose priorities may not align with broader human interests. If private companies control access to space resources, will the benefits accrue to all humanity or to shareholders? If Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos decides what happens on the moon, has humanity simply replaced national imperialism with corporate imperialism?

This tension between democratization and concentration will likely define the coming decades of space development. The outcome depends partly on regulatory frameworks—whether governments assert control over private space activities or adopt a permissive stance—and partly on the business models that emerge. Will lunar resources prove abundant enough that competition drives prices down and access broadens, or will scarcity create monopolistic chokepoints?

The View from Earth

For many observers, particularly in the developing world, the new space race can seem like an extravagant distraction. Billions lack access to clean water, adequate healthcare, or basic education. The money spent on lunar missions—whether by governments or billionaires—could address pressing terrestrial needs. This critique isn’t new; it was leveled against Apollo and remains relevant today.

Advocates respond that space development and terrestrial improvement aren’t mutually exclusive. The total global investment in space activities represents a small fraction of government budgets or global GDP. Technologies developed for space—water purification, solar panels, satellite communications—provide direct benefits to developing regions. Moreover, humanity’s long-term survival may depend on becoming a multi-planetary species, making space development a form of existential insurance.

Both perspectives contain truth. The challenge lies in ensuring that space development doesn’t become another arena where wealth and power disparities between nations and individuals widen, while also pursuing the genuine benefits that space capabilities can provide.

A New Mythology for a New Era

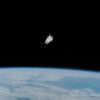

The Apollo program created a mythology that defined a generation. The image of Earthrise over the lunar horizon, Armstrong’s first step, the triumphant return of Apollo 13—these moments transcended national boundaries to become part of human heritage. They demonstrated what humanity could achieve through focused effort and inspired countless people to pursue careers in science and engineering.

The new space race is still writing its mythology. It features not astronaut heroes carefully selected by governments but billionaire entrepreneurs with controversial public personas. Its achievements—reusable rockets landing themselves, commercial spacecraft docking autonomously, rovers controlled via internet protocols—are technologically impressive but perhaps less viscerally inspiring than human footprints on virgin soil.

Yet as more diverse groups reach space, as images of Earth from the moon become commonplace rather than rare, and as the possibility of ordinary people visiting space transitions from fantasy to expensive reality, a new set of stories is emerging. These stories are messier, more commercial, and less scripted than Apollo’s carefully managed narrative. But they may ultimately prove more durable because they’re being written by a broader range of authors with more varied motivations.

The Road Ahead: Predictions and Possibilities

Where does the new lunar race lead? While specific outcomes remain uncertain, several trajectories seem probable based on current trends and capabilities.

The Next Decade (2025-2035): This period will likely see the establishment of humanity’s first sustained lunar presence. The Artemis program aims for regular crewed missions to the lunar south pole, potentially establishing the beginnings of a permanent base. Chinese crewed missions will reach the lunar surface, marking the first time since 1972 that astronauts from more than one nation have walked on the moon simultaneously (if not on the same mission). Commercial cargo delivery to the moon will become routine, with companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and emerging players establishing regular transportation services. The first in-situ resource utilization demonstrations—small-scale water extraction and processing—will prove or disprove key assumptions about lunar development’s economic viability.

The Second Phase (2035-2050): If initial resource utilization succeeds, this period could see the first true lunar industrial operations. Propellant production at scale, power generation from solar arrays built from lunar materials, and perhaps the first manufacturing of components for deep space missions. Multiple nations and commercial entities will maintain persistent lunar presence, requiring the development of governance frameworks—whether formal treaties or practical customs—to manage interaction and potential conflicts. Tourism to lunar orbit and potentially the surface will begin for extremely wealthy customers, following the pattern of early space tourism to Earth orbit.

The Long Term (Beyond 2050): Speculation becomes increasingly uncertain, but if lunar development follows optimistic projections, the moon could host thousands of people by century’s end. Permanent settlements supporting scientific research, resource extraction, manufacturing, and potentially even agriculture in sealed habitats. The moon could become the construction site for the first Mars-bound vessels, assembled from materials that never lifted off from Earth. Or it could prove economically marginal, sustaining only small scientific outposts while humanity’s attention turns to Mars, asteroids, or other destinations.

“We are at a pivot point in space history. The decisions made in the next decade will shape the next century of human space activity.”

Conclusion: A Race Without a Finish Line

The new race to the moon differs from the Apollo era in fundamental ways. Where the original Space Race had a clear finish line—putting humans on the lunar surface and returning them safely—today’s competition is open-ended. There’s no single achievement that “wins” this race. Instead, various actors pursue diverse objectives: scientific discovery, national prestige, economic return, strategic positioning, and the long-term goal of human expansion beyond Earth.

The tension between private enterprise and national space programs will likely prove productive rather than destructive. Companies bring innovation, efficiency, and capital, but struggle with long-term research without immediate commercial applications. Governments provide patient funding, coordinate international cooperation, and pursue objectives beyond profit, but often face bureaucratic constraints and political vicissitudes. The optimal path forward probably involves continued integration of these approaches, with each compensating for the other’s weaknesses.

What remains certain is that the moon will be transformed from a symbol viewed from afar into a place where humans work, research, and eventually perhaps live. Whether this transformation occurs smoothly through international cooperation or chaotically through competition and conflict depends on choices being made now, in boardrooms and legislative chambers, at launch sites and in scientific conferences.

The new race to the moon isn’t between capitalism and communism, as the Cold War space race was often framed. It’s between different visions of humanity’s future: expansion versus consolidation, cooperation versus competition, short-term profit versus long-term investment, and ultimately, the question of whether space belongs to everyone or to those with the capability and capital to reach it.

As we watch rockets from private companies and national space agencies thunder toward the moon with increasing frequency, we’re witnessing more than technological achievement. We’re watching humanity take its next halting steps toward becoming a truly spacefaring species—a transition that future generations may mark as one of the defining moments of the 21st century.

The race is on, but the destination remains uncertain. And perhaps that’s exactly as it should be. The greatest achievements often emerge not when we know the finish line, but when we dare to run toward an unknown horizon, trusting that the journey itself will reveal destinations we couldn’t have imagined when we started.