There’s a particular scene in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey that still sends chills down the spines of viewers more than fifty years after its release. It’s not the enigmatic monolith or the rebellious AI. It’s the moment when astronaut Frank Poole drifts silently into the black void of space, his severed oxygen line trailing behind him like an umbilical cord to a world he’ll never return to. No dramatic music. No sound effects. Just silence, darkness, and the terrible reality of being utterly, incomprehensibly alone.

Space has captivated humanity’s imagination since we first looked up at the stars, yet even as we’ve achieved the impossible—landing on the Moon, sending rovers to Mars, deploying telescopes that peer into the cosmic dawn—something fundamental hasn’t changed. Space still terrifies us. Not in the way a jump scare in a horror movie might, but in a deeper, more primal way that reaches into the oldest parts of our evolutionary psyche and whispers: You don’t belong here.

This terror isn’t weakness or ignorance. It’s a perfectly rational response to the most hostile environment conceivable, one that challenges every assumption our species has evolved with over millions of years. To understand why space continues to unsettle us so profoundly, we need to explore the psychology of the void, the architecture of human fear, and what happens when our deeply-wired survival instincts confront a realm where nearly everything that kept our ancestors alive becomes useless.

The Architecture of Fear: How Evolution Prepared Us for Everything Except Space

“The universe is not hostile, nor yet is it friendly. It is simply indifferent.”

— John H. Holmes

Human fear isn’t random. It’s a carefully calibrated survival mechanism honed over hundreds of thousands of years. Our ancestors who feared the rustle in the tall grass, the growl in the darkness, the edge of the cliff—those were the ones who survived to pass on their genes. Fear kept us alive.

But here’s the problem: evolution optimized us for the African savanna, for forests and plains, for environments with air and gravity and an up and down. Every fear response we possess—the quickened heartbeat, the surge of adrenaline, the impulse to run or hide—evolved in contexts where these responses could save our lives. See a predator? Run. Hear an unknown sound? Hide. Sense danger? Fight or flee.

Space renders all of these mechanisms not just useless, but potentially lethal. In the vacuum of space, there’s nowhere to run. There’s no “hiding” in a habitat module when the only thing between you and instant death is a few centimeters of metal and plastic. The fight-or-flight response becomes absurdly inadequate when the threat is the entire environment itself. You can’t fight the absence of oxygen. You can’t flee from radiation. You can’t hide from the mathematical certainty that you’re traveling through a void so vast that rescue, in any catastrophic scenario, is likely impossible.

This fundamental mismatch between our evolutionary programming and the reality of space creates a unique form of psychological distress. Psychologists have a term for it: the “overview effect”—though that typically refers to the positive cognitive shift astronauts experience. The darker side, less often discussed, is what some researchers call “cosmic dread” or “existential vertigo”—the overwhelming sensation that you are utterly insignificant, desperately vulnerable, and profoundly out of place.

The Tyranny of Silence: Why Soundless Space Unsettles Our Souls

One of the most psychologically challenging aspects of space is something that shouldn’t matter at all: the silence. In the vacuum of space, there is no sound. Not quiet. Not muted. Absolute, complete silence in a way that’s impossible to experience on Earth.

This might seem trivial compared to the genuine dangers—radiation, micrometeorites, equipment failure—but the psychological impact of this silence cannot be overstated. Sound is how we map our environment. It’s one of our primary threat detection systems. A human in a dark room can orient themselves through sound: footsteps, breathing, the hum of electronics, the whisper of air through vents. Even in the “quiet” of a room, there are dozens of subtle sounds providing constant feedback about the world around us.

Space strips all of that away.

Astronauts conducting spacewalks report that the silence is initially disorienting, then becomes oppressive. Your own breathing in your helmet becomes deafeningly loud—a constant reminder that the only sound in existence, for millions of miles in any direction, is the mechanical rasp of your own respiration. Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, who conducted the first spacewalk in 1965, later described the experience: “It was absolutely still. Such silence that you can’t imagine. You’re the only sound in the universe.”

This silence creates a profound sense of isolation because it removes one of our key connections to reality. We’re social creatures who evolved to live in groups, to communicate, to hear and be heard. The soundscape of human civilization—voices, music, the ambient noise of life—is so fundamental to our experience that we rarely notice it until it’s gone. In space, you’re severed from that web of acoustic connection. You become an island of sensation in an ocean of nothing.

The psychological research on sensory deprivation shows that humans begin to hallucinate and experience severe anxiety when deprived of sensory input for extended periods. Space doesn’t quite achieve total sensory deprivation—you can see, you can feel your body, you can hear yourself—but it removes enough of the expected sensory landscape that your brain begins to panic at the wrongness of it all. The silence of space isn’t just absence; it’s a void that your mind struggles desperately to fill.

Darkness Visible: The Terror of Cosmic Night

“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”

— Blaise Pascal, *Pensées*

Darkness in space is fundamentally different from darkness on Earth. On our planet, darkness is temporary, local, penetrable. There are stars above, a moon to provide some illumination, the promise of dawn. Even on the darkest night in the remotest wilderness, you’re surrounded by the warmth of a living planet, the presence of an atmosphere, the certainty that light exists somewhere just beyond your immediate perception.

The darkness of space is absolute. It’s not the absence of light in a place where light should be—it’s the default state of the universe. The tiny pinpricks of starlight do nothing to alleviate this darkness; if anything, they emphasize it. Those distant suns reveal just how much nothing lies between here and there. And if you drift away from your spacecraft into the shadow of a planet or moon, you enter a blackness so complete that you cannot see your own hands in front of your helmet.

Evolutionary biologists have documented that fear of the dark is nearly universal among young humans, appearing across all cultures without needing to be taught. It’s an inherited survival mechanism: darkness concealed predators, increased the risk of falls and injuries, and limited our ancestors’ primary sense. Children who feared the dark and stayed close to the fire were more likely to survive.

But the darkness our ancestors feared was filled with potential threats—things that might be lurking, watching, waiting. The darkness of space is worse because it contains nothing. There’s no predator to face, no threat to overcome, just an endless expanse of not-even-emptiness. At least a vacuum implies the removal of something that was once there. Space was never anything but void.

This distinction matters psychologically. Humans can face concrete threats with remarkable courage. We climb mountains, dive into deep oceans, enter burning buildings. But we struggle with abstract, existential threats—the kind that can’t be fought or reasoned with. The darkness of space is the ultimate abstract threat: it simply is, and it will outlast everything we’ve ever built, everything we’ve ever known, every star in the sky.

The Infinite Prison: Isolation in the Age of Connectivity

We live in an era of unprecedented connectivity. Most humans carry devices that can reach almost anyone, anywhere on Earth, in seconds. We’re so accustomed to this connectivity that even brief interruptions—a dead phone battery, a dropped call, a slow internet connection—can trigger genuine anxiety. We’ve become psychologically dependent on our ability to reach out and touch someone, even if only digitally.

Now imagine being in space. Even at the speed of light, communication with Earth from the Moon takes about 2.5 seconds round-trip. From Mars, it ranges from 8 to 48 minutes depending on orbital positions. From the edge of our solar system, messages take hours. From another star system? Decades or centuries. And if something goes wrong—if your communication system fails, if your spacecraft drifts off course, if a solar storm disrupts signals—you could find yourself not just isolated, but undiscoverable.

The Apollo 13 crisis in 1970 showcased this particular terror. When an oxygen tank exploded, the crew wasn’t just facing immediate danger; they were facing the possibility that they might die in full communication with Earth, with thousands of people listening helplessly as their air ran out. Commander Jim Lovell later recalled that one of the most psychologically difficult aspects wasn’t the danger itself but the knowledge that everyone back home knew they might die and could do nothing to help.

This creates a unique form of existential horror: being simultaneously connected and completely isolated. You can talk to people on Earth, but they’re so far away that their advice might arrive too late, their rescue attempts impossibly distant. You’re a voice transmitted across the void, a ghost speaking to the living from a realm they cannot reach.

Psychologists studying extreme isolation—in Antarctic research stations, submarine deployments, and astronaut training—have documented a phenomenon called “the third-quarter effect.” After about 60-75% of the mission duration, individuals often experience a psychological crisis characterized by depression, irritability, and a sense of unreality. The initial excitement has faded, the end still seems impossibly distant, and the accumulated stress of isolation begins to overwhelm coping mechanisms.

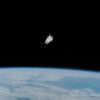

In space, this effect is amplified because the isolation isn’t just social—it’s existential. You’re not just away from other people; you’re away from your entire world, your entire reality. Every human who ever lived, except for the handful in space with you, is back on that blue marble hanging in the darkness. You’re not just isolated from individuals; you’re isolated from the totality of human experience.

The Fragility Factor: Living Inside a Catastrophe

On Earth, we live with an illusion of stability. Yes, bad things happen—accidents, natural disasters, violence—but the baseline assumption is that the environment itself is basically friendly to life. Air is everywhere. Pressure is constant. Temperature varies but within survivable ranges. If disaster strikes, there’s usually somewhere to go, someone who can help, a possibility of escape or rescue.

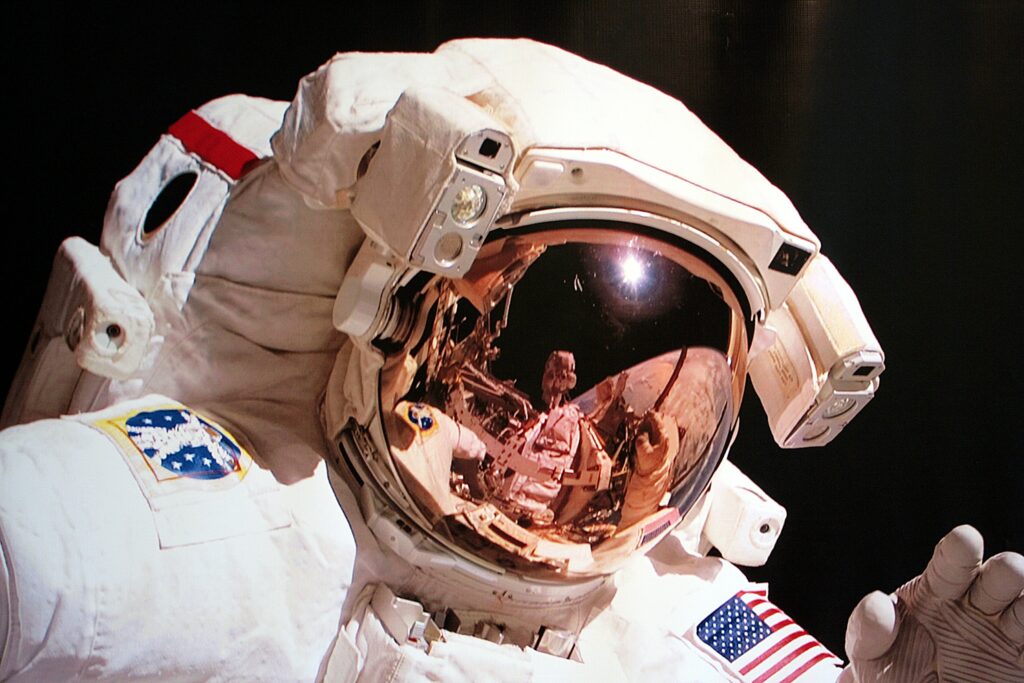

In space, you live inside a bubble of borrowed safety surrounded by conditions that will kill you instantly. Every breath you take comes from a machine that could fail. Every degree of warmth in the cold vacuum comes from systems that could malfunction. The pressure that keeps your blood from boiling exists only because of metal walls and seals that could rupture.

This creates a unique psychological burden: hyper-vigilance fatigue. You must be constantly aware that you’re in a catastrophically hostile environment, but you also must function normally enough to complete tasks, eat, sleep, and maintain your sanity. It’s like knowing you’re standing on thin ice while everyone expects you to dance.

Astronaut Chris Hadfield described this feeling in his memoir An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth: “In space, there is no problem so small that it can’t kill you.” A loose bolt becomes a projectile. A small leak becomes suffocation. A minor electrical short becomes fire in an enclosed space with no escape. Everything that would be a minor inconvenience on Earth becomes a potential death sentence.

This constant awareness that you’re living inside a catastrophe that simply hasn’t happened yet takes an immense psychological toll. Sleep becomes difficult because your subconscious knows, even if your conscious mind tries to relax, that you’re in mortal danger every moment. Dreams become vivid and often nightmarish. The body releases stress hormones continuously, leading to exhaustion that can’t be relieved by rest.

NASA and other space agencies spend enormous resources on psychological screening and support for astronauts, but there’s no real way to prepare someone for this level of sustained stress. It’s not like combat, where there are moments of intense danger followed by relative safety. In space, the danger is constant, ambient, and inescapable. You can’t take off your armor and relax because your spacecraft is your armor, and you can never leave it.

The Void Gazes Back: Existential Terror and Cosmic Insignificance

“Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.”

— Arthur C. Clarke

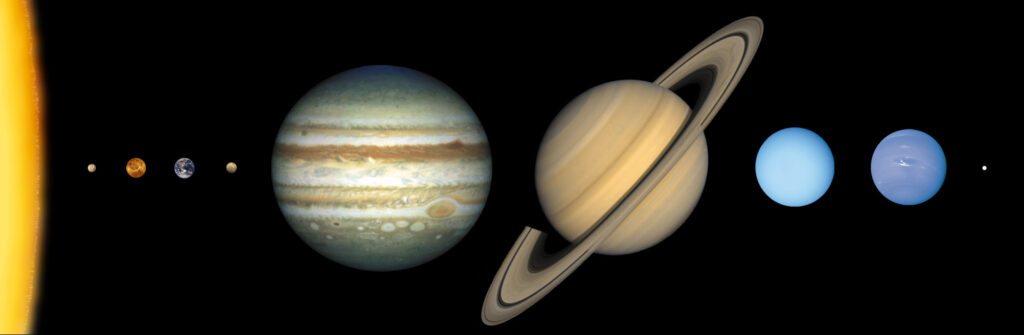

Perhaps the deepest terror of space is existential rather than physical. When humans look into the cosmic void, we’re confronted with our own staggering insignificance. This isn’t metaphorical or philosophical—it’s mathematical fact. Earth is a speck orbiting an average star in an unremarkable region of a typical galaxy, which is one of hundreds of billions of galaxies in the observable universe. The entire span of human history—everything we’ve built, everyone we’ve loved, every war fought and peace won—occupies a moment so brief on the cosmic timescale that it effectively rounds to zero.

This realization can trigger what psychologists call “existential anxiety” or what philosophers have termed “the terror of the infinite.” Unlike specific fears—heights, spiders, death—existential terror doesn’t point to a concrete threat. It’s the overwhelming sensation of meaninglessness, the gut-level understanding that the universe is indifferent to your existence, your species, your planet.

On Earth, we can distract ourselves from these thoughts. We’re surrounded by life, by the bustle of human activity, by the comfortable illusion that we matter. But in space, staring at the Earth from the International Space Station or, even more dramatically, from the Moon, that illusion evaporates. You see your entire world as a fragile blue ornament hanging in an infinite darkness, and you understand viscerally that if it blinked out of existence, the universe wouldn’t notice or care.

Many astronauts report experiencing profound psychological transformations—often positive ones, leading to greater environmental awareness and philosophical depth. But others have described periods of crushing existential dread, of feeling so small and meaningless that continuing to function requires active mental effort. Edgar Mitchell, the sixth person to walk on the Moon, described experiencing “an overwhelming sense of universal connectedness” but also admitted to periods during the mission when he felt “existentially unmoored” by the vastness surrounding him.

The Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Kovalyonok reported seeing what he described as “the melancholy of space”—a feeling that the cosmos itself was somehow sad, empty, and lonely. While this was clearly a projection of his own psychological state, it illustrates how the human mind struggles to process the scale and emptiness of space. We’re meaning-making creatures thrust into a realm where meaning seems impossible.

The Uncanny Valley of the Cosmos: Why Space Feels Wrong

There’s a phenomenon in robotics and animation called the “uncanny valley”—the observation that humanoid objects that appear almost but not quite human trigger feelings of revulsion and unease. A cartoon is fine. A photograph is fine. But something that looks 90% human and 10% wrong creates intense discomfort.

Space creates a similar psychological effect. It looks almost like somewhere you could exist. There’s visual beauty—glittering stars, colorful nebulae, stunning planetary vistas. From a distance, it seems like a place. But the moment you’re actually there, every detail is wrong in a way that creates deep psychological dissonance.

There’s light, but it doesn’t illuminate the way it should. There’s space to move, but movement doesn’t work the way it should. You can see vast distances, but there’s no sense of scale. The stars don’t twinkle. Shadows are absolute. Colors are strangely flat because there’s no atmospheric scattering. It’s a place that looks like it should be somewhere but feels like nowhere.

This wrongness extends to physical sensations. Astronauts in zero gravity initially experience what feels like perpetual falling—because that’s exactly what orbital flight is, continuous free-fall. But your inner ear, evolved to detect danger from falling, screams constant warnings that never stop. Many astronauts experience space adaptation syndrome—nausea, vertigo, disorientation—because their brains cannot reconcile what they’re seeing with what their bodies are feeling.

Your proprioception—your sense of where your body is in space—becomes unreliable. There’s no up or down, so your brain has to constantly recalculate spatial relationships. Sleep becomes difficult because your body never feels “settled.” You can’t pour water, so every time you try to drink, your instincts tell you you’re doing it wrong. You can’t walk, only push and float, so every movement requires conscious thought instead of automatic action.

This accumulation of wrongness creates constant low-level stress. Your subconscious keeps reporting: This is wrong. This is dangerous. We shouldn’t be here. And it’s not wrong. We shouldn’t be in space, at least not according to any evolutionary logic. We’re biological machines designed for a specific environment, and we’re operating catastrophically outside our design parameters.

The Mathematics of Mortality: Understanding Distance and Death

Let’s talk about the numbers, because the mathematics of space travel are themselves a source of terror once you truly understand them.

The International Space Station orbits about 400 kilometers above Earth. That’s roughly the distance from New York to Boston. If there’s an emergency on the ISS, returning to Earth takes hours—and that’s with everything working perfectly. A rescue mission? Essentially impossible within any timeframe that would matter for most emergencies.

The Moon is about 384,000 kilometers away. If something goes catastrophically wrong en route to or from the Moon, you have perhaps three days of life support, and you’re at least three days from Earth even if everything goes perfectly. There is no rescue. There is no emergency backup. You simply die, probably while in communication with people who can do nothing but listen.

Mars is, at its closest approach, about 55 million kilometers from Earth. At its farthest, 400 million kilometers. A journey takes six to nine months with current technology. If something goes wrong on Mars, you’re at least two years away from any possible rescue mission, which would need to be launched before your problem even occurred to arrive in time. In practical terms, any serious problem on Mars is a death sentence.

The nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, is 4.37 light-years away. With current propulsion technology, a journey there would take over 100,000 years. Even if we developed engines that could reach 10% of light speed—still purely theoretical—the journey would take 43 years. An entire human lifetime just to reach the nearest neighboring star system, with no hope of return, no possibility of resupply, no chance of rescue.

These aren’t just big numbers—they’re psychological weapons. They represent isolation so complete that your mind struggles to process it. They mean that any serious error is final, any major equipment failure is fatal, any medical emergency is untreatable. The distances involved strip away all the safety nets human civilization has built. You’re not just far from help; you’re so far that “help” becomes a meaningless concept.

The Silence of Adaptation: How We Might Learn to Fear Less

“Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration.”

— Frank Herbert, *Dune*

Despite all of this—the darkness, the silence, the isolation, the constant danger, the existential dread—humans are remarkably adaptable. We’re terrified of space, yes, but we go anyway. We train rigorously, we accept the risks, and hundreds of people have lived and worked in space, with more going every year.

So what changes? How do astronauts overcome these deep evolutionary fears?

The answer is complex. First, extensive psychological screening ensures that only people with particular mental resilience even attempt space missions. Second, training provides familiarity—and fear often diminishes with exposure, even in hostile environments. Third, mission design increasingly focuses on psychological support: regular communication with Earth, carefully designed schedules that provide variety and purpose, habitation modules that maximize comfort and privacy.

But most importantly, humans are meaning-making creatures. We can endure almost any discomfort if we believe it serves a purpose. Astronauts contextualize their fear within a framework of exploration, discovery, and human achievement. They’re not just enduring the terror of space—they’re pioneers, advancing human knowledge and capability. This narrative structure gives psychological shape to what would otherwise be unbearable anxiety.

Dr. Peter Suedfeld, a psychologist who has studied extreme environments extensively, coined the term “psychological immunization” to describe this process. Just as small exposures to pathogens can build immunity, carefully managed exposure to stressful situations can build psychological resilience. Astronaut training includes deliberate stress exposure: underwater training that simulates spacewalks, isolation exercises, emergency simulations. By the time astronauts actually go to space, they’ve already confronted many of their fears in controlled settings.

Additionally, focusing on concrete tasks helps manage existential dread. When you’re busy troubleshooting a CO2 scrubber or conducting a scientific experiment, you have less mental bandwidth for contemplating the vast emptiness surrounding you. Work becomes a psychological shield against the void.

The Future of Fear: What Comes Next?

As humanity extends its reach deeper into space—plans for permanent Moon bases, Mars settlements, missions to the outer solar system—these psychological challenges will intensify. A three-day trip to the Moon is psychologically manageable. A three-year mission to Mars? That will test human psychological endurance in unprecedented ways.

Space agencies and commercial space companies are investing heavily in psychological research. NASA’s Human Research Program studies isolation, confinement, and behavioral health. Virtual reality training helps astronauts prepare psychologically for the experience of space. Some researchers are even exploring whether selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or other psychiatric medications might help manage the psychological stress of long-duration missions, though this raises ethical questions about medicating people to tolerate intolerable conditions.

Fundamentally, the question isn’t whether we can eliminate the fear of space—we probably can’t, and perhaps shouldn’t. Fear is a rational response to genuine danger. The question is whether we can learn to function despite that fear, to build systems and cultures that support human psychology in profoundly inhuman environments.

Conclusion: Embracing the Terror

The terror of space isn’t something to be ashamed of or dismissed. It’s evidence that our survival instincts still work, that we accurately recognize danger when we see it. Space should terrify us. It’s the most hostile environment conceivable, a realm where literally everything is trying to kill us through simple physical law.

But terror and courage aren’t opposites. Courage is acting despite terror, moving forward even when every instinct screams to retreat. The astronauts who have ventured into space, and the many more who will follow, aren’t fearless. They’re afraid, appropriately and rationally afraid, and they go anyway.

Why? Because alongside the terror, space offers something profound: perspective. It shows us our planet as it really is—a fragile oasis in a vast desert. It reveals the universe in its terrible and awesome grandeur. It challenges us to become more than we are, to extend our small sphere of safety a little further into the infinite night.

The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote, “The poet in his solitude must converse with the being of immense spaces.” Perhaps we’re all poets in this sense, forced to find meaning and beauty in the silence that terrifies us. Space is the ultimate mirror—it shows us ourselves in the starkest possible relief. In confronting the void, we discover what we’re made of.

We may never stop being afraid of space. The darkness, the silence, the isolation, the vast indifferent emptiness—these aren’t problems to be solved but fundamental realities to be endured. But as we extend our presence beyond Earth, we’re learning to carry our fears with us, to acknowledge them without being paralyzed by them.

The silent frontier will always terrify us. But we’ll explore it anyway, one frightened, determined step at a time, pushing back against the darkness with tiny bubbles of warmth and light and stubborn human presence. Not because we’re unafraid, but because we’ve chosen to be brave.

And perhaps that’s the most human thing of all: to stare into the infinite void that should by all rights crush our spirits, and to decide that we’ll venture into it anyway, carrying our fragile light into the darkness, terrified but unbowed.